SPOILER ALERT: This review contains spoilers.

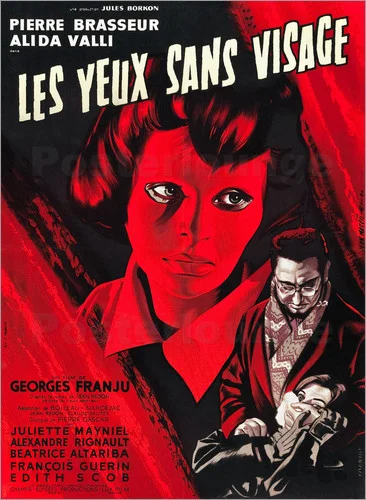

I never liked good guys. Squeaky-clean white knights riding off into the sunset with cardboard cut-out princesses were (and are) less satisfying than a troubled soul groping toward the light. That’s probably why growing up I never related to women in horror movies--they were either flawlessly good Final Girls, promiscuous Meat, or, worst of all, a nameless excuse to get some R-rated nudity in before the next gore shot. Now, with Shudder and Netflix, and more options outside of schlocky 70s and 80s horror constantly in replay on TV, I’ve been able to see more thrilling roles for women in horror. While America may just now be realizing the full narrative potential of female characters outside of time-honored T and A, in 1960, French director Georges Franju brought the world Eyes Without a Face, a brutal fable about the dangers of oppressing women and the fascism of our obsession with beauty.

Eyes Without a Face tells the story of Dr. Genessier, a brilliant surgeon who is haunted by his mutilated daughter, Christiane. Christiane’s once beautiful face was destroyed in a car accident caused by Gennessier’s reckless driving, and now, she lives in seclusion in her father’s mansion, wearing an expressionless mask and rarely speaking. She cares for the dogs and doves Genessier experiments on and tries to ignore her father’s other patients--the girls his faithful assistant Louise brings him. They’re all marginalized in some way: poor, immigrant, unwanted, and one by one, they’re tricked into taking part in a series of gruesome experiments meant to restore Christiane’s beauty. But Christiane is growing tired of being cooped up her in her father’s dismal house, and all those patients are getting harder to ignore as well…

The movie features two of the most complex female horror movie characters ever filmed. While Dr. Genessier is villain worthy of myth and many imitators (as all the knock-offs of this movie have shown), his insidious assistant Louise is equally chilling. Like Christiane, her face was destroyed in some way, the story of how and when is left ambiguous, but Dr. Genessier was able to help her, leaving her physically perfect--except for one tiny scar she conceals with a pearl necklace. Out of gratitude to Genessier, she is the friendly front of his enterprise, luring girls to his secluded clinic and their deaths. Her devotion to Genessier is as touching as it is twisted, and she provides a perfect foil to Christiane.

Made in 1960, this film prefigures the Women’s Rights Movement of that decade and the next. But instead of simple heroines oppressed by big bad men, we are given two very morally compromised women. Louise is a woman who has submitted utterly to a system that actively hates her gender. She is chained to Genessier because he rescued her beauty--the only thing a woman has to offer in a patriarchal system (other than her womb). She takes care of that need too, serving as a perverse mother figure to Christiane, telling her to keep that smothering mask on even in the privacy of her own room--What if someone saw her hideous face without it? Her devotion to beauty causes her to become a predator, hunting pretty young girls for Genessier to rip apart, all in the name of love and progress. When Christiane finally rebels, it’s fitting she stabs Louise in the operating room, the true center of her soul, the place she never really left after Genessier’s miraculous procedure gave her back her face.

Christiane is no simple avenging angel, though in her flowing white gown decked with newly freed doves she certainly looks like one. The audience is never really allowed to know the level of Christiane’s complicity in her father’s scheme. At one point, she witnesses him carrying a girl into his operating room, and a day later, he presents her with a substitute face. We don’t know how long this has been happening, but Christiane doesn’t seem surprised. At first, Christiane seems to be as monstrous as her deformities make her look, but then she turns against Louise and her father, freeing their newest victim as well as the abused animals Genessier keeps, before escaping into the woods. By killing Genessier, she forever leaves the male-dominated system. Her beauty, her place in society, even her fiancé, are all forgotten when Christiane decides to free her father’s victims.

In an earlier review, I wrote about Nosferatu’s Ellen Hutter, a heroine who spends the majority of her film weak, dependent, and on the verge of hysteria before marshalling the strength to kill the vampire. Forty years later, Christiane almost seems like the same type of heroine, but with enough differences that make her more interesting. Christiane spends her film not as a perfect porcelain doll, but as a wraith, silently nudging her father to more and more evil, but by the end, she’s found the power to move away from this--and survives. It may seem like a little step down a long road, but the fact that this film could show a morally corruptible woman openly (even savagely) defying her society and allow her to walk away triumphant from that rebellion demonstrates a growing awareness of women’s power... and their danger. While many horror movies since have been happy to make female characters either completely innocent or entirely wicked, Christiane Genessier finely straddles these two lines, creating a truly chilling horror movie heroine.

Pennie Sublime