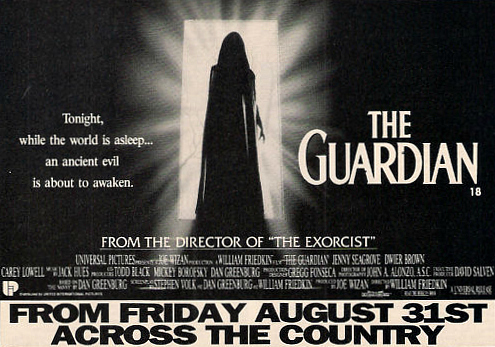

ROCK-A- BYE(-BYE) BABY: WILLIAM FRIEDKIN'S LOST HORROR FILM, THE GUARDIAN

Sometimes, lightning strikes twice. It happened for Coppola with Godfather I and II; it happened for James Cameron with Terminator I and II. For Martin Scorsese, it’s happened so many times that he spends his off-season working as an electrical conductor for Yellowstone. Back in 1990, a lot of folks were hoping that it was going to happen, too, for William Friedkin, director of The Exorcist. After making what is, arguably, the greatest horror film of all time, Friedkin nominally retired from the genre, spending the 1980s directing neo-noirs and Laura Brannigan music videos (a noble endeavor, to be sure). Then, in 1990, word came down that Friedkin was finally ready to let inner demons out again with The Guardian (out now on DVD from Scream Factory). Everything seemed in place for there to be a second Friedkin horror masterpiece: Like The Exorcist, The Guardian was based on a best-selling novel (Dan Greenburg’s The Nanny), and, like The Exorcist, it dealt with a child under assault from supernatural forces. The only difference was, this time around, the pustule-laden demon was replaced by a Druid priestess with a penchant for ritual nudity—if nothing else, a point that would compel a few non-horror fans into theater seats. Things were looking up for both Friedkin and cinematic horror as a whole in 1990.

Show of hands: How many of you reading this have ever heard of The Guardian?

Exactly.

In the dying days of the 1980s, yuppie couple Phil and Kate find themselves in desperate need of a nanny to tend to their newborn son, Jake. Their prayers are apparently answered in the form of Camilla, a young, sweet British woman who, although childless herself, possesses a natural rapport with kids. The instant Camilla picks Jake up, his incessant crying stops, and a peaceful new chapter begins in the lives of Phil and Kate. This is a horror movie, of course, so, instead of everyone learning life lessons and Camilla getting paired off with a sweet young nerd at the end of the movie, things have to get real. And real do they get. Camilla isn’t any young nanny, but the last in a line of Druid priestesses who performed human sacrifices in veneration of a tree-dwelling demon whom they’ve brought to the New World. Every guy in the movie may have eyes for Camilla, but there’s only one male in whom she has any interest: Jake, and if she has her say, the little guy is going to be the main course in a very unusual dinner.

It’s difficult to say what exactly is wrong with The Guardian; it defies criticism not necessarily by being bad, but by failing to be good. That failure, however, isn’t on the monumental scale that would afford it a place on Mystery Science Theater 3000. It’s not even bland-bad, in a “That movie sucked and I’m never watching it again” sort of way. The acting isn’t so terrible; the electronic score is appropriate to its’ time-frame; there are even some decent scares (which I’ll address later). There are several hanging plot threads (a pivotal scene insinuates that the demon’s victims can be restored to life once it’s defeated, an idea that’s never addressed again), but, they’re not so glaring as to harm the integrity of the film per se. No, the biggest sin The Guardian commits is one of mediocrity. Everyone knows that Friedkin can do better, but an amateur could’ve also done worse. Why doesn’t anyone remember The Guardian? It’s just not that memorable.

Which is a shame.

Because, buried beneath layers of apathy, laziness, and downright sloppiness is an idea that could’ve worked; and, in those rare instances when the film does work, it works beautifully. The casting of Jenny Seagrove is a revelation: poised, elegant, and ethereally beautiful, Seagrove is the kind of woman who knights would’ve written courtly poems about, and she plays her role in a sly, easy way that’s deeply troubling in hindsight, because Camilla is the kind of woman any parents would want watching their kid. It’s always easy to see a horror movie and think that, if you were in that situation, you wouldn’t pick up the creepy hitchhiker or run upstairs to escape the knife-wielding maniac. It’s much more difficult to think that you’d be the one person to see through a mask of sanity when there’s no reason to exist that the sanity is a mask in the first place. Wisely, Seagrove plays her role without an iota of menace: Even after she’s been found out by Phil, she doesn’t crack in the slightest, from the subtlest of wicked smiles to a spiteful glare. There are, after all, other people around for whom to keep up appearances, and in-universe it wouldn’t make sense for Camilla to let Phil think he’s right, even for a moment. Other actresses would’ve attempted to imbue Camilla with a sinister edge at a certain point, but Seagrove was wise enough to treat the character intelligently.

Seagove’s casting brings me to another one of the film’s strong points: It knows how to inject real, human moments into the script (co-written by Friedkin, Greenburg, and Stephen Volk). Early in the film, Kate worries that her pregnancy has rendered her no longer sexually attractive. Later, the couple have a frank discussion after they first meet Camilla in which Kate worries that Camilla’s presence in the house might become a sexual temptation for Phil. They’re very real conversations revealing very real worries, and they’re written and acted in such a way so as to give them a slice-of-life quality. Another, similar moment occurs later in the film between Kate and her friend, Ned, who she’s set up with Camilla. The two have been dating a while, but Camilla keeps Ned at a distance because, as the audience knows, her true love is the tree demon. However, from Kate’s perspective, Camilla’s a shy young woman in a foreign country who wants Ned to make the first move in taking their relationship to a physical level, and she encourages Ned to try and catch up to her on her way home from work and surprise her with a romantic evening. I’ll talk about the aftermath of that scene below (it’s one of the film’s best moments), but the brief interaction between Ned and Kate speaks volumes about their characters without saying anything at all—a talent sadly lost on many a genre writer and director. (Sadly, Friedkin and company decided to jettison some of that subtlety by clumsily injecting a subplot in which Camilla attempts to seduce Phil. Though it could have served some narrative purpose, it doesn’t, beyond providing some excuses to see Ms. Seagrove in the buff. The movie very vaguely hints that Camilla’s wannabe-seduction of Phil may serve some ulterior motive, but in execution, it never seems like anything more than mutual lust).

Now, about that “romantic evening.” Much of what I’ve said about The Guardian up to this point could apply to a great number of films; but there’s one sequence in The Guardian which elevates it from the status of “I watched this movie last week, whatever” to “Deserve to be remembered,” and that’s the series of events resulting from Ned trying to catch up to Camilla on her way home. I mentioned earlier that the third credited screenwriter on The Guardian is a gentleman named Stephen Volk, the brains behind Ghostwatch. For those in need of a quick lesson in notorious genre films, Ghostwatch was a made-for-television BBC production that only aired once, on Halloween night, 1992. The film ultimately proved so disturbing that the BBC has never aired it again, and it’s cited in psychiatric literature as being the first film to induce diagnosable PTSD in adolescents. Keeping in mind Friedkin’s reputation for The Exorcist, it’s no surprise that they’d manage to create one truly memorable, truly frightening sequence; if there’s anything wrong with the “romantic evening,” it’s that the entire movie wasn’t like this.

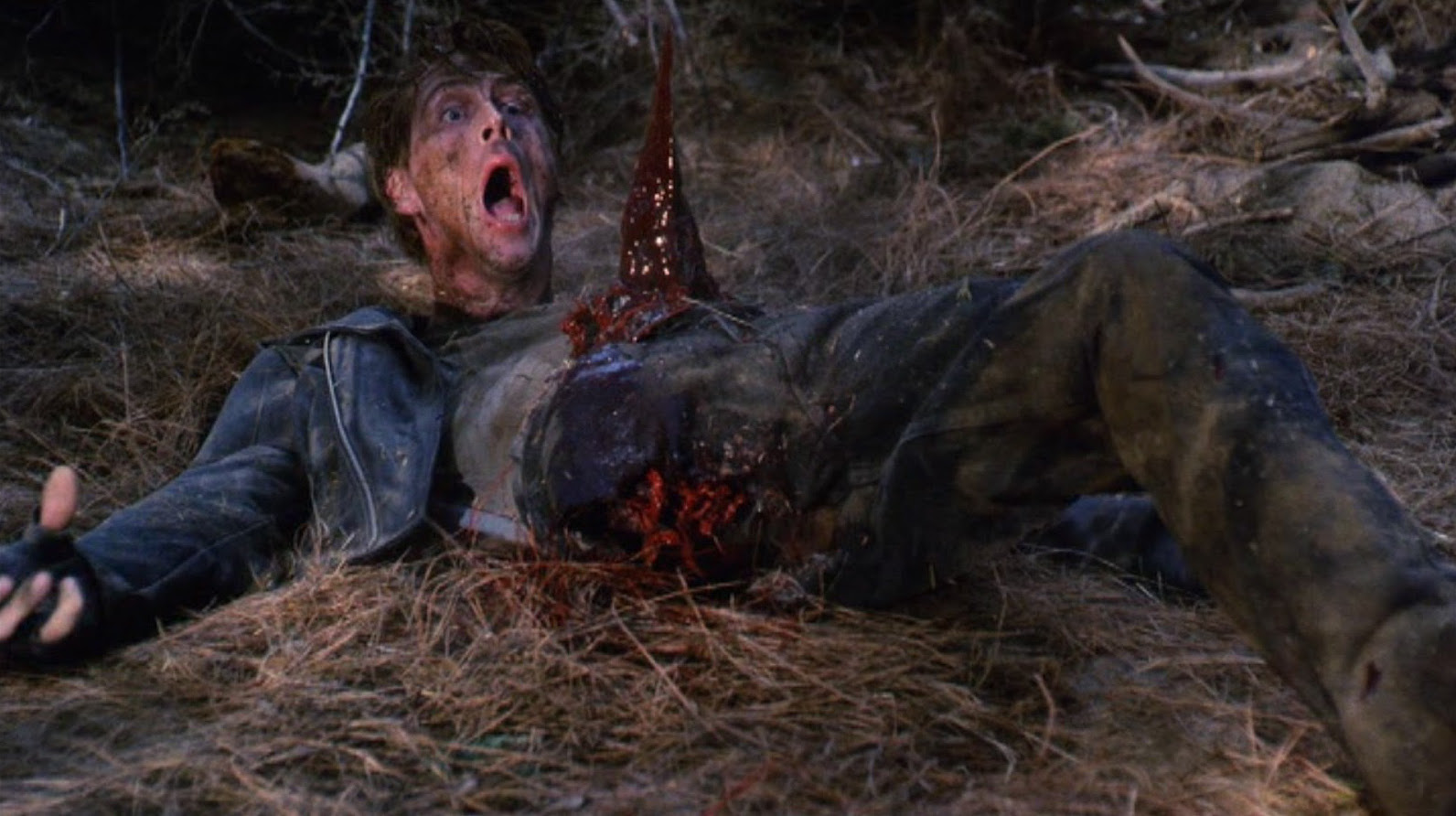

Heeding Kate’s advice, Ned does indeed catch up to Camilla. Rather than find a waiting lover, though, she’s cavorting naked in the moonlight with a pack of wolf familiars and the demon-tree. What follows is an exercise in deliberate protraction: For the next several minutes, the wolves chase Ned through the woods; through the streets of LA; through his own backyard; and ultimately inside his house, where chase sequence becomes home invasion set piece. Despite the length of the sequence, it never becomes dull or feels drawn out. Ned has already been established as a likeable character, so there’s vested audience interest in his survival—despite her personal apathy for him, not even Camila seems very interested in seeing him actually die. On top of that, he proves himself unusually adept for a horror movie victim: Upon reaching his house, he calls the police, but wisely lies and claims that he’s being attacked by coyotes—a real peril in 1980s California. What’s more, unlike virtually everyone in the history of horror movies ever, Ned owns a gun and knows how to use it. When the wolves finally corner him, Ned doesn’t go down without a fight: He goes down firing off 00 buckshot, and damn if he wouldn’t have survived if his pursuers weren’t infernal in origin.

It’s telling that The Guardian is one of the few films that Friedkin has declined to talk about at length. Matter of fact, it’s one of only two, along with 1983’s Deal of the Century, that’s absent from his autobiography, The Friedkin Connection. Some interpret this absence as a personal recognition of the film’s flaws; however, there’s a second camp with their own theory, one which makes a great deal of sense and shines a different light on the film. Hollywood lore has it Friedkin was never meant to direct The Guardian in the first place. Rather, that mantle was intended for Sam Raimi, he of The Evil Dead. It makes a lot of sense: The tree-demon, which gets virtually no development (has he always been around? Did Camilla somehow conjur him? Does he need the babies to stay alive, or just because he’s a dick?), wouldn’t have needed any more motivation than “because he’s an evil tree” in a Sam Raimi movie, and there’s even an attack scene in the script that plays out as a gender-reversed version of Evil Dead’s infamous tree rape. On top of this, whenever the tree-demon comes into play, what’s otherwise a very viscerally restrained film lets its’ gore flag fly, with enough gallons of fake blood gushing forth from both the tree and its’ victims to put Pete Jackson to shame. They’re very kooky elements for what attempts to be a spooky film, and they speak to having been written for a director much more comfortable with, and accomplished in, horror comedies. Worth even more consideration is that contemporary reviews of Greenburg’s The Nanny viewed it not as a straight-up horror novel, but rather as a parody of Ira Levin’s high-brow horror novels of the 1960s and 70s (the central conceit: Yuppies are so inculturated to city life that they think nature is literally going to eat their kids). When viewed through this lens, it’s easy to see where the movie goes wrong, because Friedkin is attempting to impose a straight genre reading on a story that calls for the exact opposite (and it’s here that anecdotes about Friedkin and Volk’s attempts to smooth out Greenburg’s script causing Volk to suffer a breakdown begin to make sense). Where Friedkin goes for domestic drama, he should be aiming for Lifetime-style overwrought melodrama. Where he aims for shock scares involving bloodthirsty trees, he should be playing up the absurdity of the situation. Rather than a triumphant return to horror, Friedkin should’ve been aiming for a new notch in his belt: horror comedian. It’s doubtful that The Guardian ever had the makings of a new classic in the Friedkin canon, but it at least would have been much more memorable, and perhaps allowed the film’s few truly worthy moments to be more widely remembered.

Preston Fassel