LOST AND FOUND IN OKLAHOMA: MANIAC! (THE OTHER ONE)

Anyone and everyone who’s ever browsed a DVD section (or watched the Sci-Fi channel) knows about the mockbuster: The ultra-low budget, dubiously constructed ripoff of whatever is big at the movies at a given moment. In the wake of Snakes on a Plane there was Snakes on a Train; when Transformers hit big screens, Transmorphers hit the Redbox. For hardcore aficionados of the rental store or the bargain bin, they’re sort of the comic relief for long, dry, browsing periods, something to give you a chuckle when you’ve grown frustrated that the special-edition Blu-ray 25th Anniversary widescreen edition of Hellraiser really is out of stock. For as wide ranging as my circle of horror, sci-fi, exploitation, and grindhouse friends is, comparatively few of them have ever actually seen one of these movies (although I consider myself blessed to actually number among my friends some really awesome people who’ve actually been in a few of them. You know who you are, and you rock). Aside from parents who pick up the riffs on more kid-friendly flicks, there’s a very specialized subset of fans who routinely watch these movies: The hardcore MST3Kies who like to host their own RiffTrax sessions; avowed b-movie fans who genuine appreciate a low-grade film; people for whom massive amounts of T&A need a little more context than the Internet’s vast porno repository can provide. They’re a small but dedicated crowd, and I salute them—you are keeping a proud tradition alive.

Because, you see, these sort of obscure movies weren’t always so obscure.

Perhaps one of the strangest features of the grindhouse and exploitation scene of the 1970s and 80s were the number of sleazy remakes of Hollywood movies that it produced. There were, after all, still dollars to be made by putting together hastily made, poorly conceived versions of someone else’s hard work, and by tossing in a little bit of blood and boob, the powers that be could draw in members of the filmgoing public for whom The Exorcist was just a wee bit tame. Depending on your geographic location, and the sort of clientele your local neighborhood theater marketed towards, you could watch Conan the Barbarian one week and, if you thought that wasn’t quite enough, return the next to watch Ator the Invincible for the same story with an incest subplot. You or check out Rosemary’s Baby in one cineplex before hopping across town to see The Devil Inside Her for some down-‘n-dirty dwarf action. To see such blatant cinematic plagiarism on the bigscreen would have been a surreal experience, if not for the regularity with which it occurred; it could probably be successfully argued that this business model helped to keep the Italian horror film industry afloat for a good decade. No, what was really surreal were the actors who actually appeared in these movies. A good source of comic fodder is the number of places that once-established celebrities go once their careers hit a snag (or outright die): Infomercials, syndicated television shows, reality TV. Several once established horror icons have, of course, kept food on their tables by appearing in films of dubious quality, though seeing someone with a good level of name recognition pop up in something significantly beneath his or her talent can be good for a quick laugh. What was bizarre about mockbuster making as it existed in the heyday of the 70s and 80s was how they often featured high-profile celebrities who hadn’t necessarily hit a snag in their careers yet. Somehow—through offer of money, threat of violence, or some other means—celebrities with profiles like Richard Burton and Leslie Uggams could inexplicably turn up in the sleaziest film at the box office around the same time they were winning legitimate critical acclaim elsewhere. This is what brings us around to my inaugural segment of Lost and Found in Oklahoma: 1977’s MANIAC!

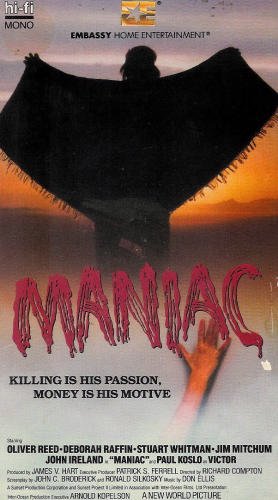

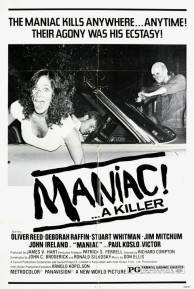

Maniac! was one of my first forays into the cult section at Hollywood Video; I was, admittedly, fooled into thinking that it was the William Lustig film of the same name (the distributor’s intention—some of the rerelease art aimed at the grindhouse market blatantly tries to convolute the films), and rented it after having read for years on teh internets what an insane piece of cinematic depravity the Spinell flick was supposed to be. It seemed that, if I was going to start watching subversive cinema, I might as well start right at the bottom; also, I figured, if I was going to see something nasty, better to see something nasty that I could prepare myself for. What I got was far from nasty, though, in a way, it was far, far weirder than what Mr. Lustig or Mr. Spinell would make a few years later.

In the resort town of Paradise, Arizona, a Native American named Victor stalks the night with a high-powered crossbow, randomly killing cops and leaving behind cryptic messages alluding to the oppression of his people and demanding butt-tons of money in exchange for not engaging in an indiscriminate killing spree. The town is home to an unusually high number of millionaires, and, being corrupt businessmen in a late-70s sleaze movie, they decide that the best solution to the problem is to take it out of the hands of conventional police officers and turn the case over to Nick McCormack, a rough-and-tumble soldier-of-fortune type who shoots first, drinks second, and asks questions if he feels like it later. As the town gears up for a festival and sexy, sexy reporters descend on Paradise to cover Nick’s hunt for the killer,alliances will be formed, friends will be betrayed, and lots of pseudo-mysticism will be spouted before the climactic showdown in the McDowell Mountains leaves more than just the viewer’s attention span clinging to life.

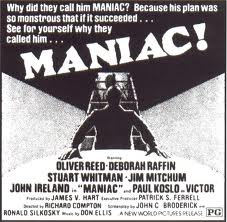

Originally marketed under the titles Ransom and The Ransom (some grindhouse markets were apparently more demanding of their articles), Maniac! is, of course, a cash-in on Dirty Harry, made about six years too late. While the Clint Eastwood film helped to spawn/popularize the rogue cop subgenre, I’m unaware of any other film that, rather than follow the same formula, just blatantly rips off the plot. What’s most confusing is that this was released six years after the original Dirty Harry came out, and one year after the most recent Dirty Harry sequel, 1976’s The Enforcer. It could be argued that Maniac! was simply a belated attempt to cash in on The Enforcer, but that begs the question of why the effort was taken to plagiarize the first film in the series rather than the most recent.

As I said, though, these sort of ripoffs weren’t so rare at the time, and, other than the timing, there’s nothing really so special about a Dirty Harry clone making it to the big screens in the 1970s (other than the fact that it took two people to write it, one of whom, Ronald Silkosky, also cowrote 1970s clunky Dunwich Horror). What is surprising is the actor who turns up in the role of Nick McCormick, the film’s ersatz Harry Callahan: It’s Oliver Reed.

Reed’s always enjoyed something of a troubled reputation: Even during his lifetime, his status as one of the world’s greatest actors was under constant threat of being eclipsed by his status as one of the world’s greatest drinkers: James Bond impresario Albert Broccoli famously wrote that, but for Reed’s image as a party animal, he’d have replaced Connery as the star of the franchise. Following Reed’s death, the more troubled corners of his life have taken even more of a center stage in the minds of film fans, especially the tale of his untimely demise, which holds that his fatal heart attack was presaged by an arm wrestling match with a bunch of sailors and the consumption of nearly $1000 worth of booze in a single sitting at a Maltese pub. It’s difficult, then, to remember that, when Reed was in fine form, he was a very fine actor, and that for all of the misses of his career (in addition to the Bond role, Reed’s drinking also allegedly cost him parts in Jaws, The Sting, and an unidentified Steve McQueen Movie), Reed spent more of it up than he did down. This is what makes his appearance in Maniac so fascinating: It came out during one of those up periods. The previous year, he appeared in the eminent Burnt Offerings with Bette Davis and Karen Black; within two years, he’d be delivering a career-defining performance in David Cronenberg’s The Brood. Hell, the same year that Reed made Maniac! he starred in Crossed Swords, a high-profile family film, alongside Raquel Welch, Ernest Borgnine, and George C. Scott, all powerhouses at the top of their careers. Why, then—and how—did Reed end up in Maniac!?

The obvious answer is booze money: While Reed’s authorized biography, What Fresh Lunacy is This, neglects to mention how Reed ended up making Maniac!, it does include anecdotes from costar Paul Koslo, who recalls that Reed showed up to the script’s 6am table read toting a literal goblet of booze and already trashed out of his mind, a state in which he remained for the duration of the shoot (although both Koslo and director Richard Compton recall that Reed was the consummate professional once the cameras began rolling). That Reed was heinously drunk during filming was something I surmised on my first viewing, before I became aware of Reed’s reputation: Although his clenched-tooth delivery might just be an attempt to ape Eastwood’s trademark speech, it’s hard to say the same of the profuse sweat that keeps cropping up on Reed’s brow even when all of his costars remain bone dry, or the way that he sometimes speaks his lines just a few seconds later than seems appropriate.

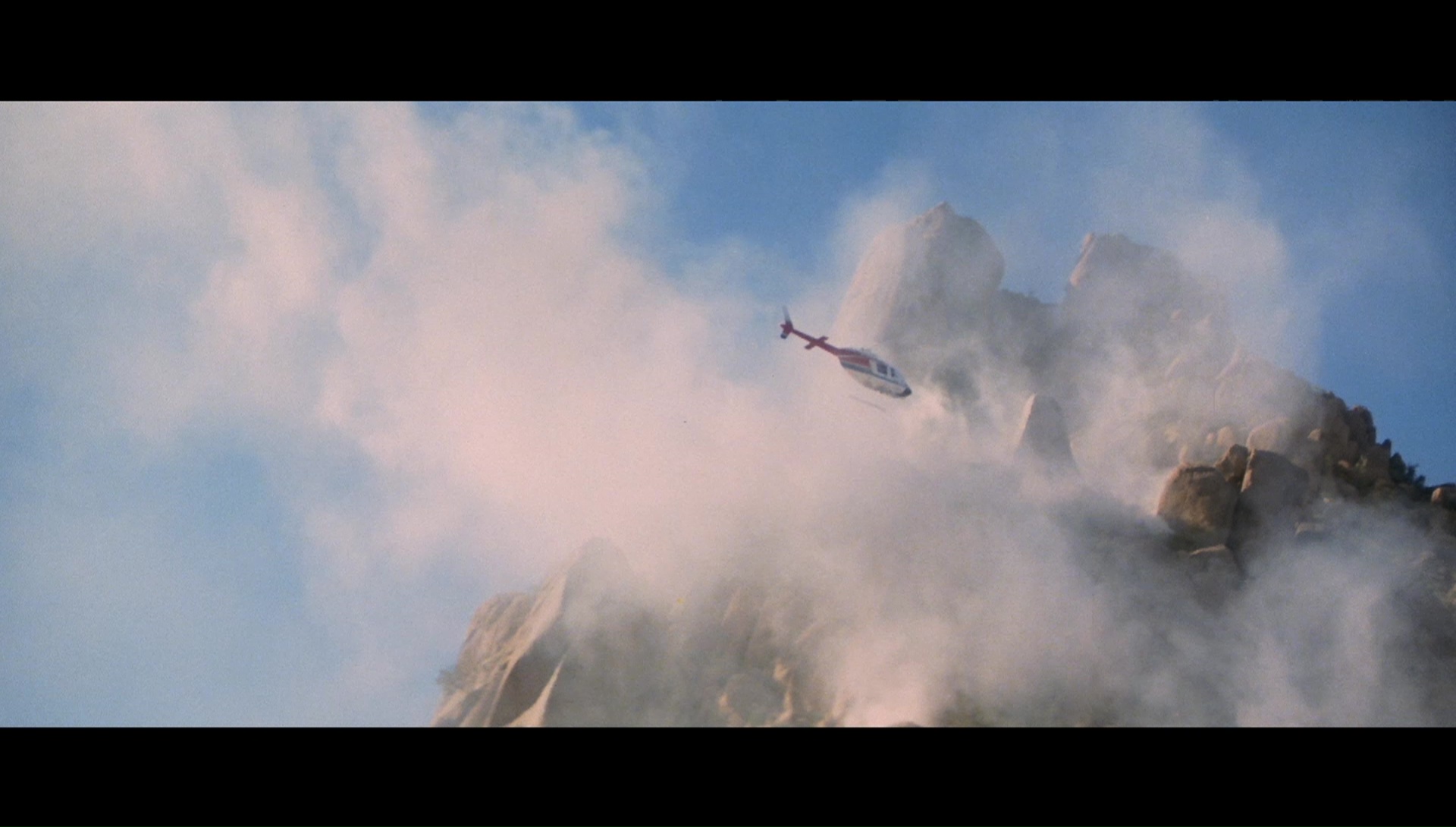

In a way, it’s this very drunkenness that serves as an indicator for how the rest of the movie plays out. Some cash-ins are hilariously bad: MST3K featured more than a few of them during the show’s run. Some are actually good, and become classics in their own rights: Its’ reputation has led many from remembering that Zombi/Zombi 2 started out as a cash-grab on Dawn of the Dead. Maniac! is neither end of this spectrum: It’s a slow, confused, middling movie that sometimes almost reaches one extreme or the other before comfortably settling back to mediocrity, the way that a pub philosopher might stumble onto some grain of insight before slurring back into incomprehensibility. Take the location shooting: The movie was filmed in and around Phoenix, Arizona, a rare place to shoot any film, let alone a low-budget exploitation flick. It was a brave choice that almost pays off: If anything can be said for Maniac! it’s one of the few motion pictures to try and really display the state’s natural beauty, which really gets shown off by some astounding aerial photography during a couple of chase sequences and the film’s climax. For the most part, though, the city’s majesty is only superficially featured here; as nice as it is to look at, neither the cinematographer nor director ever capture the environs the way that, say, John Carpenter made the viewer feel the cold of British Columbia in The Thing. Rather than really exploit the setting, it’s just an interesting backdrop against which the story unfolds, and other than the cat-and-mouse chase in the mountains, it just as easily could’ve been set in New York or LA.

Much the same can be said for the film’s plot. Though Nick is introduced fairly early on, and you’d expect him to start kicking ass and taking names shortly thereafter, the story moves at a glacial pace that isn’t helped by the muddy audio and Reed’s occasionally muffled delivery. In fact, while I’ve seen the movie a total of three times, there’s a particular plot element that the film’s latter half hinges on which I still haven’t quite figured out, largely because I can’t understand what anyone’s saying in the pivotal scene. It might be helpful, because I think it delivers an in-universe explanation for why Victor the Native American looks whiter than Meryl Streep. I fell asleep the first time I tried to watch Maniac! and, to this day, I don’t think I’ve ever watched it all the way through in a single setting.

Complicating matters further is that it can’t quite figure out what it wants to be. The movie was meant for the drive-in and expy circuits, and as I already mentioned, these sort of remakes tended to inject some subversive element into the original formula; but, if anything, Dirty Harry ends up as the dirtier of the two films. Maniac!’s shootouts are too tame to market it as an action movie; the killings are too bloodless to make it a slasher; the “mystery” element is too downplayed to make it a neo-noir; and the attractive women are too few and too clothed to appeal to the horndog crowd. This last point, especially, underscores the film’s incongruities. Though the female characters are smart, persistence, and not mere sex objects, that’s exactly how all of the male characters treat them. In the space of five minutes, McCormick meets a reporter, she annoys him, he threatens her life, she gets randy, and they have consensual sex. It’s the sort of atavistic attitude you’d expect from something born of 1950s’ lad culture, and it’s hard to tell if the writers were attempting to be ironic or if they really thought that intelligent women are sexually aroused by having revolvers shoved into their faces. There’s just no textual evidence in the script to let the audience know exactly how they’re supposed to react to everything. The case could be made that story and characterization were the screenwriters’ priorities and that the movie was meant to explore themes like trauma and capitalism in an exploitation context, but neither plot nor character are developed enough to make this a “serious” grindhouse movie in the vein of Who Killed Teddy Bear?

So what’s the final verdict on Maniac!? Strangely, despite the fact I’ve spent most of this review running it down, it’s not exactly a movie I hate; in fact, it’s sort of a sentimental film for me. It was one of my first forays into the real realm of grindhouse films, and a VHS copy of it sat on a shelf above my bed during my last year of high school, finally making the trip with me to Texas before I traded it to a guy for a copy of Marjoe. Even before I rented it, I’d spent years of my childhood glimpsing its’ seedy, bargain-basement cover art, wondering what sort of nightmarish depravity it might contain. As a matter of fact, I’m once again in possession of a copy, which now sits alongside the real Maniac on my DVD shelf. The sheer absurdity of it makes it a great conversation piece with other grindhouse fans who’ve never heard of it. For all of its’ faults, it’s a movie I just can’t not own. That’s the funny thing about bad movies, and, I suppose, pop culture in general: One guy’s trash really is another man’s treasure, even if the guy who considers a treasure also happens to think it’s kinda trash at the same time.

Preston Fassel