In a way, the career of John Waters reflects the evolution of exploitation cinema itself. Starting out in the 1960s with black-and-white microbudget shorts that didn’t so much have narratives as they were a series of shocking, hallucinogenic set pieces, he moved on in the early 1970s to more coherent feature films that were still more shock than substance (Multiple Maniacs, Pink Flamingos, Female Trouble). In the latter part of the decade and early 80s, he reached a comfortable midpoint, releasing pictures that still retained a certain grindhouse quality while focusing more on conventional storytelling (Desperate Living, Polyester). The late 80s and early 90s saw him releasing films with a mainstream ethos, palatable to the masses with just the slightest undercurrent of dissolution (Hairspray, Cry Baby), before one last return to earlier form amidst the grindhouse revival of the early 2000s (A Dirty Shame). That Waters’ last film should come out during both a period of reinvigorated interest in exploitation cinema and the dawn of reality TV culture illustrates a fascinating point about his career, and the trajectory of popular culture: It may not be possible for Waters to make an impact today, because reality has come to reflect the once-mythical worlds of filth depicted in his movies. From the trailer-park shenanigans of Honey Boo-Boo and Mama June to the glamorous squalor of the Kardashians, the once underground ethos of Waters’ works has become part of the mainstream fabric of American pop-culture. Taken in that context, Serial Mom—now on Blu-ray from Scream Factory—occupies a fascinating place in Waters’ catalogue. It’s the point when mainstream America embraced John Waters, the perfect, bizarre intersection between Waters doing what he did best and the rest of the world—for the first time—readily accepting it.

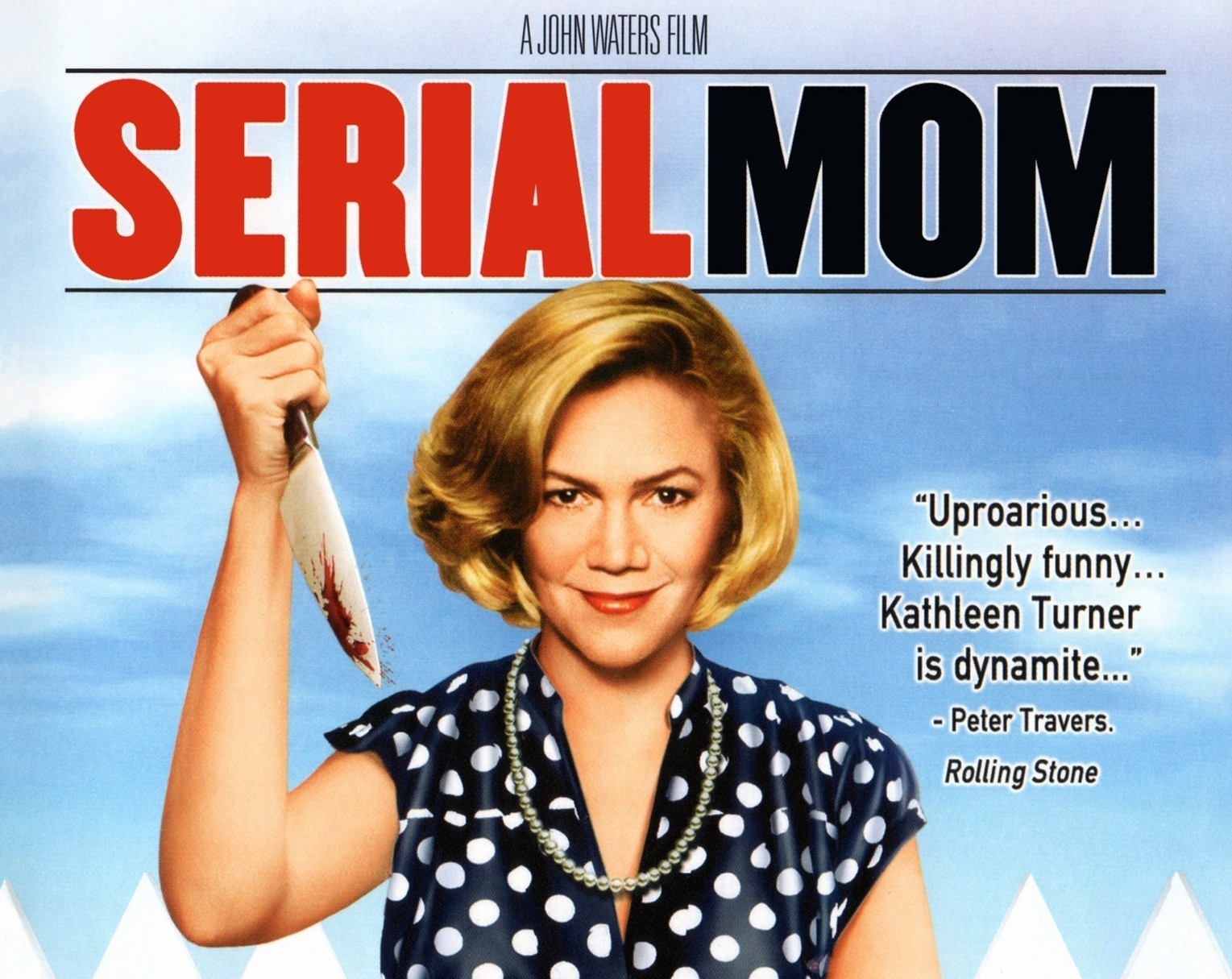

Beverly Sutphin (Kathleen Turner) is a woman out of Emily Post's darkest fever dream. Polite and well-mannered, she's a loving wife to her husband, Eugene, a doting mother to her kids Misty and Chip, and spends her days happily keeping house in her idyllic Baltimore home. She's also a deranged serial killer, so obsessed with etiquette and maintaining appearances that merely wearing white after Labor Day is enough to send her into a murderous rampage. It’s not quite clear exactly how long Beverly has been this way, but we’re apparently coming into her life at a moment when whatever control she was able to exert in the past is slipping. She certainly hasn’t gotten this far in life by committing murders so public as running over her son’s teacher for questioning whether the boy has a good home life, or taking a fireplace poker to Misty’s crush in a public restroom when he fails to reciprocate the girl’s affections. It’s no surprise when the police finally catch up to Beverly, but, ultimately, the joke may be on the system: At trial, Beverly wows the jury with both her Betty Crocker wholesomeness and a lifetime of legal knowledge built up from studying other serial killers, and before long, she may be free to walk the streets once more…

Though I didn’t know it at the time, Serial Mom is how I first became aware of John Waters. It was heavily advertised at video stores when it came out on VHS, and I saw prominent displays and posters at both the Dierburgs and Schnucks’ video stores in St. Louis during my many trips there as a child. It went into heavy rotation on cable after its’ theatrical run, and I count it among the many movies I shouldn’t have sneaked a peak at on television when no one else was around. I had no idea what I was seeing at the time. I knew that there was something not quite right about it. I’d secretly watched R-rated movies before, but this was different, forbidden in a unique way I couldn’t articulate. It wasn’t until nearly a decade later that I made the connection, when my first girlfriend gave me a DVD of Pink Flamingos and Female Trouble for my birthday (and, yes, I realize now that should’ve been the first warning sign). Suddenly, it all did and didn’t make sense. It made sense in the way that, of course, anything by the man who made Pink Flamingos would carry with it a sense of taintedness; it didn’t make sense that the man who made Pink Flamingos would ever get a mainstream release with advertisements in grocery store video departments.

It was the kind of things a John Waters movie would parody.

That, I think, is what really makes Serial Mom so fascinating. It’s not just a bizarre entry in Waters’ oeuvre—it’s as mainstream as he ever got while still embracing the style, themes, and ethos that made him famous to begin with— but it’s now a cultural artifact. In the 1990s, trashiness became en vogue. For something to be cool, it had to be “extreme.” Altruism was out. Ultra-violence and hypersexuality were in. It was an age that had no tolerance for moderation, chastity, or humility. One need look no further than the all-encompassing success of the WWE during its’ “Attitude Era” to see what the latter part of the decade was all about. The company rose to mainstream prominence because it tapped into a cultural desire for good guys to be replaced with amoral anti-heroes and villains with soulless psychopaths; for the women to be as nude as possible and the violence bloody as possible. Every week, millions of people tuned in to watch the exploits of a cross-dressing sex offender, a devil-worshipping biker, and a "heroic," homicidal redneck.

In other words, the world had begun to look an awful lot like a John Waters movie.

It’s no surprise in that context that Serial Mom would not just come out of this era, but be so readily embraced by it. In his attempt to ostensibly lampoon the fetishization of 1950s suburban culture, Waters unknowingly encapsulated something very true about the 1990s. Beverly is, strangely, a sort of stand-in for Waters and his career as they existed at the time: Polite, articulate, and friendly, Beverly is also a harbinger of death and dissolution who, against all expectations, finds herself warmly embraced by the world not just in spite of her crimes, but because of them. He’d also predicted, strangely, the coming of his own irrelevancy as a filmmaker and the beginning of his position as an elder statesman of pop culture. Waters’ career had always flourished because his films depicted an un-reality: a nightmare world based on drag aesthetics and campiness-on-acid. It was a world that, if it existed it all, did so only on the periphrery of society. As time went on, though, Waters lived to see the lifestyle he depicted in his films—what was always a sub-sub-culture at best—slip into the mainstream. The cultural critic had become cultural soothsayer, and his greatest prophecy would foretell his own decline.

All of this, of course, ignores Serial Mom on its’ own merits; and taken on its’ own merits, it is a very funny film, one that expertly combines Waters’ signature sleaziness with a broader, more accessible style of comedy. Scream Factory has paid apt tribute to the film both as an entry in Waters’ catalog and its’ cultural significance with one of their trademark Blu-rays. The centerpiece of the special features is a new interview with Waters, Turner, and Mink Stole, one of the last surviving members of Waters’ Dreamland Players. On top of that is a pair of featurettes—“Serial Mom: Surreal Moments” and “The Kings of Gore: Herschel Gordon Lewis and David Friedman,” as well as a making of feature and the theatrical trailer. The real gold, though, is that there isn’t one but TWO commentaries from Waters—one solo, one with Turner. As anyone who’s ever listened to a Waters commentary knows, they’re almost as good (and sometimes better) than the films themselves. He’s got a keen critical eye not just for his own work but for pop culture as a whole, and his conversational style and witty delivery of personal stories makes listening to him the same as Sunday afternoon at your eccentric uncle’s house.

For fans of Waters, black comedies, or just those fascinated by the evolution of pop culture, Serial Mom isn’t just a good investment, it’s downright mandatory. Just as long as you don’t buy it on Sunday. Beverly wouldn’t like that.

Preston Fassel