The 1990s was a difficult time for horror. After the monumental success it enjoyed in the 1980s, it appeared as if the genre had briefly lost its way, with the great wave of the slashers giving way to a veritable wasteland in the first half of the decade; and while Wes Craven’s Scream helped to make fright cinema relevant again, it wouldn’t be until the early 00s’ that consistently quality films began to appear again in the numbers they’d once enjoyed. As such, it makes sense that a confused, frustrated decade would give birth to some confused, frustrated franchises. One need look no further than Hellraiser, Leprechaun, I Know What You Did Last Summer, and Wishmaster to see that, while the powers-that-be had their thumbs firmly on horror fans’ pulses in the 80s, they lost the ability to read it in the 90s. What could’ve been effective series in different hands were instead relegated to messes so jumbled that many entries in their respective series couldn’t maintain consistent quality (or logic) from scene to scene, let alone entry-to-entry; and while the burgeoning direct-to-video market made it profitable for studios to continue churning out product, regardless of reception, it’s no surprise that no one or two franchises really rose up to define the 90s the way Friday the 13th and A Nightmare on Elm Street so personified the 80s.

And that’s a shame.

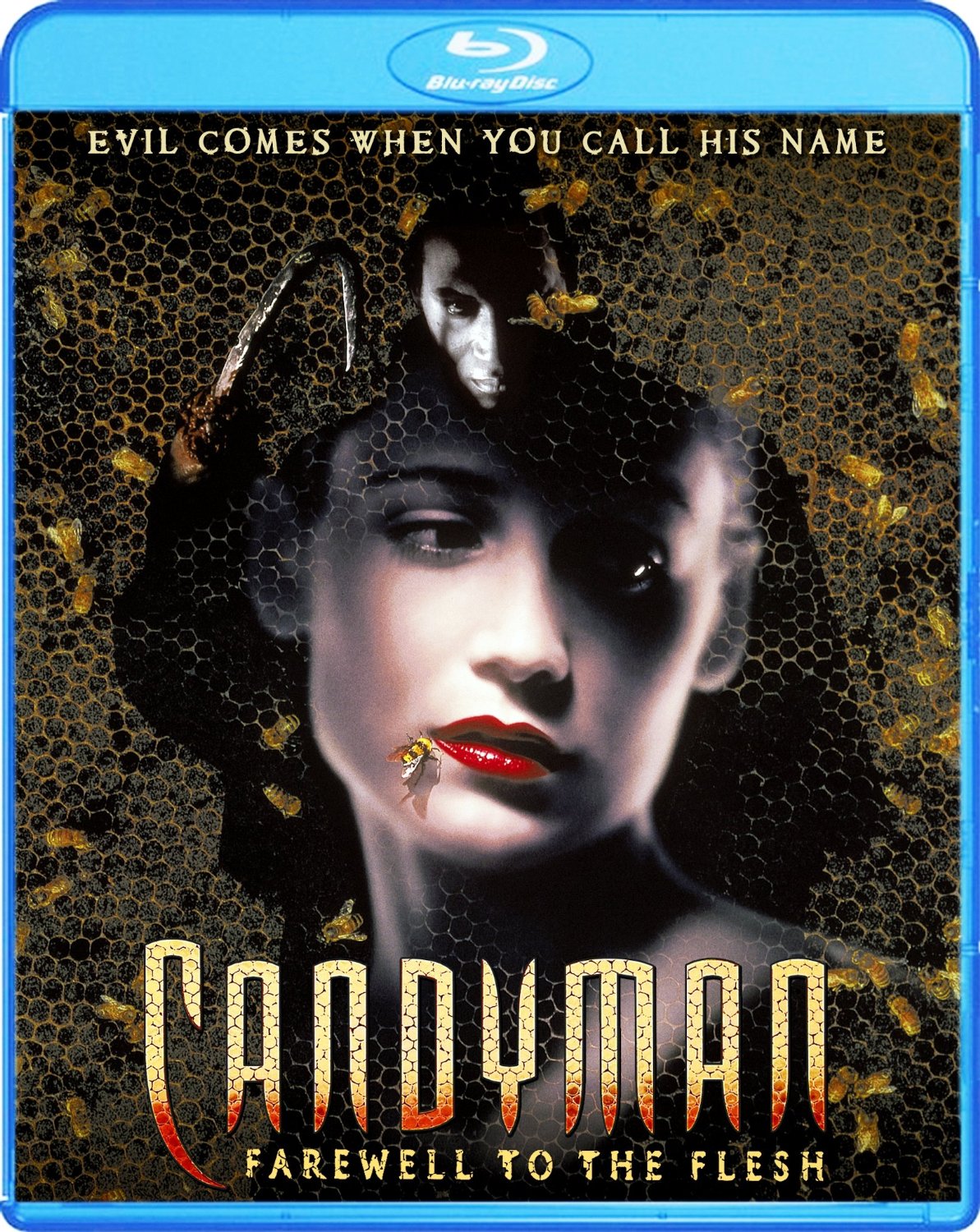

Because buried amongst those messes were more than a few flickers of hope for something that really could have let the 90s stand out as a stellar decade. Perhaps chief amongst those flickers is the Candyman franchise. Unfortunately, the series never completely delivered on the promises it made with the first entry in the series; and, as is so often the case, its’ rapid deterioration was already present in its’ second out, Candyman: Farewell to the Flesh, now available on Blu-ray from Scream Factory.

It’s the lead up to Mardi Gras in New Orleans, and the Tarrant family could use some of the absolution promised by the upcoming Lenten season: Decades ago, family patriarch was brutally murdered during an occult ritual of his own design, tarnishing the Tarrant name and ensuring an everlasting stigma for his widow, Octavia (Veronica Cartwright), and children Annie (Kelly Rowan) and Ethan (Kelly Rowan). While Octavia has buried her pain in booze and Annie has vanished into the New Orleans slums, teaching art to disadvantaged children at a charter school, Ethan has sought solace in mania—namely, his very vocal, very public assertions that his father was killed by The Candyman (Tony Todd), the vengeful spirit of a black artist lynched for his affair with a white woman. For his latest demonstration, Ethan assaults a prominent scholar in a New Orleans bar, after taking umbrage with the man’s latest book, which counts The Candyman as just another urban legend; and when the scholar later turns up dead, himself a victim of the angry ghost (who shares Ethan’s frustration with being called mythical), Ethan is the first and only suspect. In the wake of her brother’s arrest, Annie attempts to assuage her students’ fears that the Candyman is real by attempting to summon him up; unfortunately, she’s about to learn that her brother’s suspicions were more than accurate, and when The Candyman comes calling for her, his grudge is more personal than most…

To say that Farewell to the Flesh is a bad movie wouldn’t be entirely accurate. As a matter of fact, much of the film’s disappoint comes from the final third of its’ ninety-minute running time, which fails to deliver on all of the spectacular promises made by the first hour. For the first sixty minutes, it seems as though Farewell is on its’ way to establishing a franchise even as it redefines its’ predecessor in the series. The characterization is beautifully rich, especially for a sequel, with the script by Rand Ravich and Mark Kruger instilling the story with a sort of Tennessee Williams epic family drama that fits nicely within the Candyman mythos. While it’d have been easy to characterize Octavia as a drunken loon and Ethan as the “oh-crap-he-was-right” crazy guy, the writers have instead made them fully realized human beings, very realistically reacting to the burden of carrying a family shame in a culture where the concept of “family shame” still exists. Cartwright, especially, turns in a solid performance as the grieving matriarch, giving the role a tortured vivacity that makes her sympathetic in spite of her grandiosity. The pair also succeed in the difficult task of making a concept into a character—in this case, Mardi Gras, which acts not only as a setting for the action but also a force within the story, with the film’s action mirroring the progress of the celebration. A running commentary by the exhuberent DJ Kingfisher, outlining the history of Mardi Gras and goings-on around the city, lend the film an air of big things happening, also helping to enhance the dread as his broadcasts act as a sort of countdown for Annie’s inevitable final confrontation with The Candyman.

That said, the film does fall apart at roughly the one-hour mark; and when it does, it’s a complete mess. Though Rowan is able to hold her own when she has more experienced and more lively costars to play against, once Annie takes center stage following The Candyman’s inevitable killing spree, she shows that she wasn’t quite ready to carry an entire film at this stage in her career. Though Tony Todd is admirable in his attempts to salvage the film, he simply wasn’t given quite enough to work with; for as much thought went into the characterization of the Tarrant family, the titular character is woefully underutilized and underdeveloped. Though monsters of a certain caliber tend to work best when they aren’t seen too often, The Candyman is a articulate, intelligent, thoughtful force; and with an actor of Todd’s caliber in the part, the character deserved much more than he was given. As The Candyman himself points out near the film’s climax, he isn’t—at least, in theory—a bad guy. As a matter of fact, prior to his lynching, he was a downright pacifist; and while history is full of stories of the wronged dead returning as vengeful spirits, The Candyman’s motivation for indiscriminate murder—which is fully articulated during a woefully ill-conceived flashback sequence—paints him more as a petulant high schooler than an avenger of racial violence. With the seeds of a powerful message regarding race relations and the history of intermarriage in the United States, the character’s arc could have been much more compelling, especially considering his twistedly altruistic motivation for his grudge match with Annie; anything relevant that the writers wanted to say, though, is lost in a messy sludge of incongruously gristly murders and a series of increasingly irrational character decisions.

Yet in spite of its’ flaws, Farewell to the Flesh is worth a glance, if not an extended look. Scream Factory’s transfer deserves particular praise; it ranks as some of the best work the company has done, bringing to Blu-ray all of the fantastically sleazy, Skinemax-inspired aesthetics of mid-90s horror films. For all of its’ other failings, horror cinema in the 90s truly succeeded in creating a unique look for the decade’s genre fare, and it’s on display here in all of its’ squalorous glory. The disc also contains new interviews with Tony Todd and Veronica Cartwright, as well as new commentary from director Bill Condon, who has achieved fame of late for his role in bringing us—shudder—Twilight: Breaking Dawn.

The film’s most endearing feature, though, is easily the presence of Todd himself. Despite his failure to completely salvage the film, watching Tony Todd bomb is sort of like watching a much lesser actor succeed; the man is beautifully charismatic no matter what he’s in, and seeing him perform here is a reminder that we’re blessed he decided to become an actor rather than a model. He would only play Candyman once more—in the appropriately direct-to-video Day of the Dead—and it’s a shame that he was never given the opportunity to more fully embody the character the way that Robert Englund or Doug Bradley did Freddy and Pinhead. The Candyman could have been the slasher for the 90s—a socially relevant figure in an era known for its’ attention to political correctness and reassessment of race relations. It is, perhaps, a testament to the character’s efficacy that the 90s was such a wasteland of generic-teeny bopper horror, in which the powers-that-be would rather advance least-common denominator dreck rather to protect the sensitive eyes who might have found offense at the idea of a black villain-protagonist.

Preston Fassel